As ever, a lot has happened over the last month in the life sciences, but fear not, as we have been keeping an eye out for the month’s best stories. Here is our monthly run-down of the science that amused and amazed us here at BioStrata, be sure to check back every month to satisfy your thirst.

Stingrays take time to chew things over

Straight off, we bet you haven’t given munch (sorry) thought about how creatures eat. But here’s an interesting fact, did you know that aside from mammals, most animals don’t chew? The majority of the time animals like crocodiles and sharks opt to tear chunks from their lunch and swallow it down whole. Stingrays have, it seems, more manners. In one of the most appetizing videos of the year, scientists show a stingray chowing down on a tasty morsel, giving it a good chew before throwing it down the hatch. The chomping-action enables the rays to extract vital nutrients from the insects in their diet. Before the discovery, scientists were wondering how the rays were able to access these nutrients, as simply swallowing the bugs without giving them a good chew would see them pass through the system. Tasty news indeed!

Not a tall tale

Their secret is finally out; the giraffe population is not homogenous, but split into four distinct species. Previously, scientists grouped them into various subspecies based on coat pattern, but taking a closer look at their genes has revealed that they are in fact comprised of four species that don’t interbreed in the wild. Even though these lanky even-toed ungulates are not exactly inconspicuous, we understand why this has not been identified earlier (after all a giraffe is a giraffe). Owing to a lack of an obvious geographical barrier needed for speciation, giraffes’ proclivity for mobility, and the fact that they are just so handsome, zoologists are understandably scratching their heads as to why we don’t just have one big happy giraffe family. What a pain in the neck.

Micro-munchers

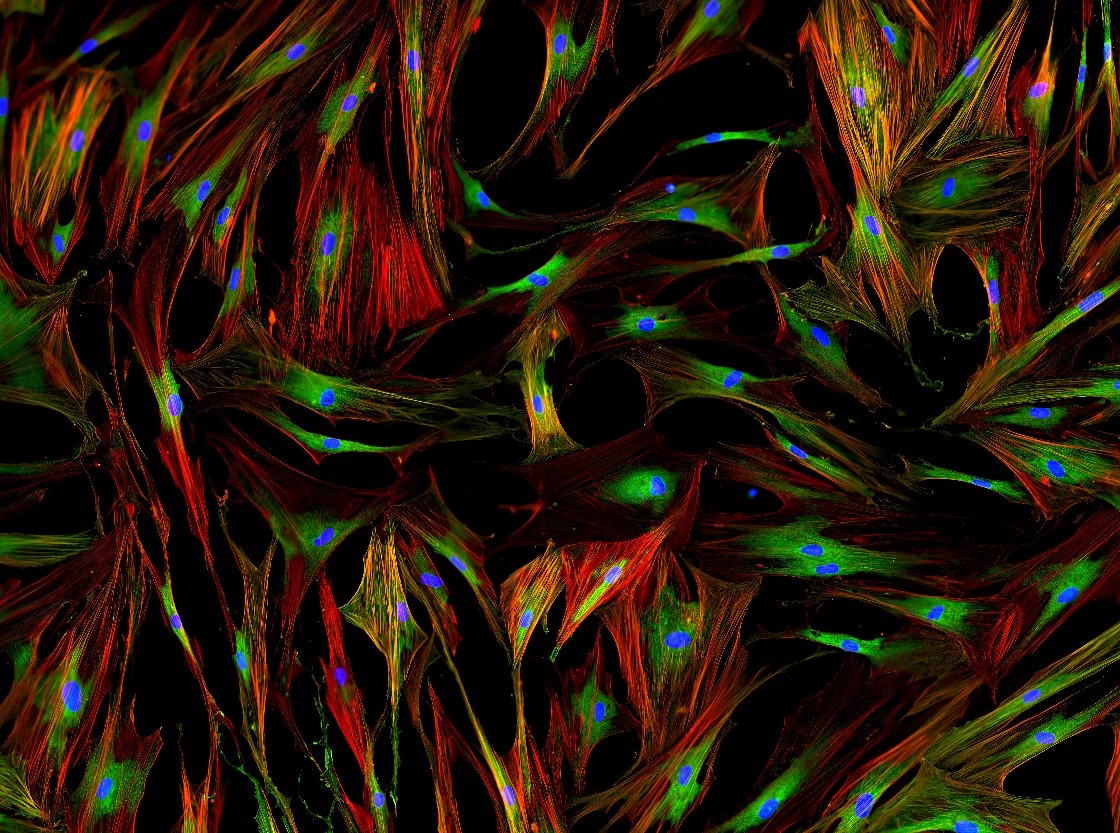

It turns out, some cells have a funny way of saying hello. Scientists observing intercellular interactions have shown that rather than a brisk handshake or a warm hug, cells meeting up like to take bites out of each other. As with everything in science, the process has a name: bidirectional trans-endocytosis, and is followed by the cells parting ways for good. It transpires that when cells have finished exchanging information via protein interactions, the quickest and easiest way for them to dissociate is to engulf the neighbouring protein complexes, rather than detach themselves more gently. We seriously hope this doesn’t catch on with us multicellular organisms, as our clients probably don’t consider us to be that tasty.

Image: Damian Ryszawy/Shutterstock.com

Tardi-great!

Chubby, microscopic, and near-indestructible. We’re not talking about toddlers, but Tardigrades – the eight-legged micro-animals that frequent almost any moist environment. Also known as water bears, these interesting little critters are the only known animals that can survive the low oxygen and high radiation conditions of space. Now scientists have identified a Tardigrade protein that confers resistance to damaging X-rays – and have been able to transfer these legitimate superpowers to human cells! The protein known as Dsup prevents DNA X-ray damage, and human cells that expressed the protein were able to reduce damage by a whopping 40%. We hope scientists are looking at other superpowers that we may be able to steal. Our hope is on superfast typing, but we don’t think Tardigrades are that good at using computers.

Cancer out of hiding

There’s no denying it; cancer is sneaky, but day-by-day scientists are uncovering its secrets. Researchers have long been puzzled by the fact that the body’s otherwise pretty powerful immune system – apt at dealing with primary tumours and diseases in many unpleasant forms – can be suddenly bamboozled as soon as cancers gain the ability to metastasise. Some scientists think they have an idea of what’s going on, following the discovery of a loss of interleukin-33 production in metastatic tumours.

The researchers stipulate that this loss of IL-33 (a key mediator of the immune response to cancer) means the immune system is no longer able to recognise the tumour cells, allowing them to spread unchallenged. What’s exciting about this is that the researchers found that putting IL-33 back into the cancer cells rendered them partly susceptible to the immune system, which was able to recognize the tumours once more.

If you’d like to be kept up to date with all the latest news in science and marketing, subscribe to our monthly newsletter. Always valuable, interesting content. Never any spam.